For the children and grandchildren of the 750,000 people expelled from their homes in 1948 from Palestine, the Nakba, or catastrophe in English, is simultaneously a moment of the past, the violent reality of the present, and a fear of the future.

The stories of their ancestors are not just a set of inherited facts or a prologue – they are a living, breathing presence that informs how they think, move, work, and exist.

Thursday marked the second Nakba Day since Israel’s war on Gaza began in October 2023, and the weight of this day is heavier now than ever for the Palestinian diaspora. For those who live in the US, their ancestral trauma has interwoven itself with their intense frustrations of being American.

For many young Palestinian Americans, this clash has led to major life shifts – transforming their careers, relationships, priorities, and sense of self, as the goal of return to Palestine becomes the axis around which their lives now turn.

Some of the Palestinians interviewed by Middle East Eye preferred only to use their first names to protect themselves from any potential consequences from employers and/or universities.

‘Why should I just live in America when I can be in Palestine?’

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

For the majority of Palestinians, a “return” to the homeland is hypothetical. But for Rebhi, 28, it is real.

Both of his parents’ families were displaced during the Nakba from Haifa and West Jerusalem. His paternal grandparents fled to Egypt before settling in Jordan, where the generations that followed have remained. His maternal grandparents eventually settled in Nablus, where they received Palestinian citizenship, or their “hawiya”, after 1967.

Rebhi’s mother passed her West Bank citizenship on to her children, a right that few mothers have in the Arab world, making Rebhi one of the few “privileged” dual-citizen Palestinian Americans.

“I’m privileged as a Palestinian in the sense that I have a hawiya. I can legally exercise my right of return and genuinely be here,” he said. “I’ve always kind of felt this way, but after October 7, I really felt like I needed to actually do it.” The war in Gaza erupted after the Hamas-led attacks on southern Israel on 7 October 2023.

‘I have a hawiya … I can legally exercise my right of return and genuinely be here’

– Rebhi, Palestinian American

Like many Palestinians, Rebhi found himself adopting the role of an educator on Palestine around his peers. But since Israel’s war on Gaza, which has killed more than 53,000 people, he felt that he needed to become politically active.

But even after investing more time in a nonprofit he founded with his mother before 7 October 2023, Doctors Against Genocide, he was overcome with his disillusionment in working in corporate America.

“It wasn’t really like a life where I just sit around amassing wealth to donate,” he said.

“I kind of lost purpose, I guess, in the idea of just working, being a coder, giving my talents to some VC (venture capital firm) and paying half my taxes to America – contributing tangibly with my finances and my labour to the system and to the country that is playing a massive part in the destruction of my people.”

Now, Rebhi owns a start-up in the occupied West Bank where he works with local coders and developers.

“Why should I just live in America when I can be in Palestine and contribute tangibly to my community? My labour can actually impact Palestinians, instead of just having some little bank be happy that I put in a shift.”

Rebhi says he feels fulfilled and has an opportunity to continue the life his grandparents would’ve lived, were they not displaced from Palestine, and connect with the family that remained in East Jerusalem after 1948.

“Part of the reason why I wanted to come back was to reconnect our family that stayed in Khalil and make sure that we maintain our roots there so that Israel doesn’t win with their goal of displacement and destruction of these roots.”

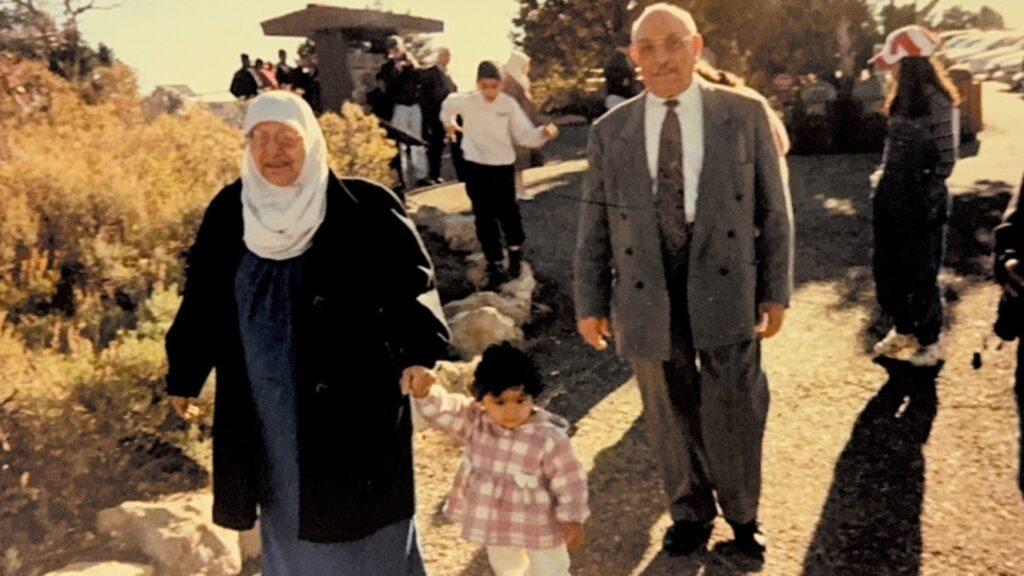

It hasn’t escaped him that his grandfather, whose name he carries, was displaced from Jerusalem at the same age that Rebhi is now. Rebhi went back to Palestine in December 2024.

“In the 70s, there was a displaced Rebhi who couldn’t go back to Khalil. And now, there’s me, Rebhi, who’s in Khalil. It’s a circular story, in a sense.”

Now, as Rebhi watches Gaza, he feels that the level of carnage is exponentially worse than what his grandparents endured during the Nakba, which is widely considered the lowest point in Palestinian history.

“Comparing then and now almost feels disrespectful to the destruction happening in Gaza. Not that it was easy during the Nakba – of course, it was devastating. But this is a whole other level.”

‘Restoring what was broken’

Rana’s great-grandparents lived in Lydd before they fled in 1948, and her extended family scattered across the occupied West Bank. This fragmentation, she says, has shaped every generation since.

“I am still figuring out what role I play in this cause, but I believe that being Palestinian is the biggest test and honour of my life,” Rana, 26, said.

For her, return isn’t just physical.

“It’s about restoring what was broken.”

“There are family members I’ve never met, not because they don’t exist, but because displacement turned borders into permanent barriers.”

Like many Nakba survivors, Rana’s grandparents often spoke of the home they left with a “sacred longing”. They highlighted the lush land, the neighbours, the smells, the community, and the olive trees.

“I often think about how so much of what my ancestors endured wasn’t written down or seen,” she said.

“It makes me want to witness harder, speak louder, and remember more. At the same time, I’m moved by what they protected – stories, values, traditions. Despite everything, they passed them down.”

Although Rana’s identity as a Palestinian was always solidified by visiting her family in the occupied West Bank throughout her childhood, she says that after Israel’s war on Gaza, she is unapologetic about having it be shown now, regardless of any consequences for her career.

“I used to be more cautious about being openly Palestinian, worried about how people would react, what it might cost me professionally or socially. But I’m not scared anymore. If anything, I’ve never felt prouder or more certain about claiming that identity publicly and unapologetically.”

‘Catastrophe’ doesn’t encapsulate it’

Lillian Albelbaisi, 25, can recite the entire story of her grandparents’ last day in Qaqun, a village near Tulkarm, in 1948.

Her grandfather, Jamil, was only 13 when he fled alone to a nearby village, sustaining an injury from Israeli bombardment in the process. A piece of shrapnel remained in his leg until the day he died from cancer in 2012.

Her grandmother, Niameh, fled with her mother to Tulkarm, where her father brought along with him the key to his home and a paint can. He had unfinished housework that he thought he would get back to after the Israeli military left.

As Abelbaisi watches Gaza, the historical parallel is ever present. The scenes of roads filled with images of displacement, tent cities that seem to stretch for miles, and people realising that the homes they assumed they would return to do not exist anymore are too obvious to miss.

But, like Rebhi, she feels that the ongoing atrocities in Gaza do not fit within the confines of her ancestors’ traumas.

“There’s no human definition that can define what these people have done. I do think the Nakba never ended. Everything has been a continuation of the next. But right now, I don’t think we can even call it just ‘Nakba’. ‘Catastrophe’ just doesn’t encapsulate it at all.”

Something sparked in Abelbaisi once Israel’s assault on the enclave began: she needed to absorb anything and everything that she could, which was produced in Palestine. She poured herself into history, into any existing footage, and, most deeply, into literature.

“I just started reading like crazy,” she said. “We have so many themes, we have so many motifs, we have so many things that we can talk about just in Palestinian literature alone.”

Her intellectual pursuits, combined with becoming more politically active in organising for Palestine in Washington DC, led her to the same realisation that pushed Rebhi to abandon all that he worked for in the US. Her job at a think tank began to make her feel “gross”.

The war on Gaza “fundamentally changed what I want in life and where I want to work. I can’t work somewhere where I don’t feel good about what I’m doing.”

It culminated in her quitting her job and entering a role that could give her peace of mind, no matter how it affected her career trajectory. But like the rest of the descendants, her US citizenship stands in the way of fully living her life guilt-free.

The Gaza war ‘fundamentally changed what I want in life and where I want to work’

– Lillian Abelbaisi, Palestinian American

“As a librarian, I feel a bit better,” she said. “But I know that nothing’s going to completely clear my conscience.”

A return to Palestine for the diaspora is something that Abelbaisi has taught herself to work towards, but not because she wants it in her lifetime.

“In the end, it’s not about me personally seeing a free Palestine, it’s me ensuring that I’m helping us reach that goal,” she said.

Abelbaisi says the 77-year struggle has given her solace, as it is a war of “endurance, not a battle of strength”.

“And that’s Israel’s biggest fear – is that we’re going to continue to endure. And unfortunately for them, we will endure because that’s what we know best.”

‘It’s become all-consuming’

For Nadeen, 28, a descendant of Palestinians who were expelled during Israel’s brutal siege of Yaffa in April 1948, the goal of return has been an awakening.

Growing up, she knew she was Palestinian and proud of it, but the trauma that followed her mother’s family, who lived in tents in Gaza for a year before being exiled to Kuwait, weighed so heavily on them that it silenced the stories from being told.

It wasn’t until she witnessed the horror unfolding in Gaza that she realised how little she knew of the stories that gave shape to her own.

“My family has a very, very hard time discussing difficult things. They had a hard time discussing Palestine with us. And I wish that wasn’t the case.”

This discomfort was passed down to her parents, who now live in Texas, where her father, who suffers from dementia, watches the graphic videos coming from Gaza every day, finding himself retraumatised over and over.

Now, Nadeen is more intent on learning the details she never knew existed and mourning the ones she’ll never get to know.

“There’s so much lost history because it’s all been consumed by so much trauma,” she said.

“I just wish we had some semblance of normalcy so I could remember my ancestors as who they truly were, and not just these people who constantly had to survive something bigger than them.”

However, the identity that remained primarily in the background of her childhood has now become the lens through which she sees everything she encounters.

“As soon as this genocide started, I became super disciplined with myself and what kind of things I consume,” she said. “What kind of things I purchase, what kind of things I engage with, who I hang out with – it was all related back to Palestine. I couldn’t look at a meal without thinking about Palestine. I couldn’t drink anything without thinking about Palestine. I couldn’t dress myself without thinking about Palestine. It’s become very all-consuming for me.”

The reinforcing of her identity, Nadeen says, has strengthened her bond with her family. Both of her parents speak of their childhoods, their time in Kuwait during the First and Second Intifadas, and what they remember from the stories they would catch here and there.

Similar to Rebhi and Abelbaisi, Nadeen has re-examined how her actions and labour in the US impact Palestine, both good and bad. As she helps organise protests in New York, building a community of Palestinians that she has never had before, she has become disillusioned with her job in tech.

She has now set her eyes on entering a master’s programme in psychology, where she hopes to focus on the traumas of immigrants and people of colour.

This, she says, is an ode to her ancestors, whose trauma was never acknowledged.