CNN

—

From day to day, Donald Trump’s second term often seems like a roman candle of grievance, with the administration spraying attacks in all directions on institutions and individuals the president considers hostile.

Hardly a day goes by without Trump pressuring some new target: escalating his campaign against Harvard by trying to bar the university from enrolling foreign students; deriding musicians Bruce Springsteen and Taylor Swift on social media; and issuing barely veiled threats against Walmart and Apple around the companies’ responses to his tariffs.

Trump’s panoramic belligerence may appear as to lack a more powerful unifying theme than lashing out at anything, or anyone, who has caught his eye. But to many experts, the confrontations Trump has instigated since returning to the White House are all directed toward a common, and audacious, goal: undermining the separation of powers that represents a foundational principle of the Constitution.

While debates about the proper boundaries of presidential authority have persisted for generations, many historians and constitutional experts believe Trump’s attempt to centralize power over American life differs from his predecessors’ not only in degree, but in kind.

At various points in our history, presidents have pursued individual aspects of Trump’s blueprint for maximizing presidential clout. But none have combined Trump’s determination to sideline Congress; circumvent the courts; enforce untrammeled control over the executive branch; and mobilize the full might of the federal government against all those he considers impediments to his plans: state and local governments and elements of civil society such as law firms, universities and nonprofit groups, and even private individuals.

“The sheer level of aggression and the speed at which (the administration has) moved ” is unprecedented, said Paul Pierson, a political scientist at the University of California at Berkeley. “They are engaging in a whole range of behaviors that I think are clearly breaking through conventional understandings of what the law says, and of what the Constitution says.”

Yuval Levin, director of social, cultural and constitutional studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, also believes that Trump is pursuing the most expansive vision of presidential power since Woodrow Wilson over a century ago.

But Levin believes Trump’s campaign will backfire by compelling the Supreme Court to resist his excesses and more explicitly limit presidential authority. “I think it is likely that the presidency as an institution will emerge from these four years weaker and not stronger,” Levin wrote in an email. “The reaction that Trump’s excessive assertiveness will draw from the Court will backfire against the executive branch in the long run.”

Other analysts, to put it mildly, are less optimistic that this Supreme Court, with its six-member Republican-appointed majority, will stop Trump from augmenting his power to the point of destabilizing the constitutional system. It remains uncertain whether any institution in the intricate political system that the nation’s founders devised can do so.

One defining characteristic of Trump’s second term is that he’s moving simultaneously against all of the checks and balances the Constitution established to constrain the arbitrary exercise of presidential power.

He’s marginalized Congress by virtually dismantling agencies authorized by statute, claiming the right to impound funds Congress has authorized; openly announcing he won’t enforce laws he opposes (like the statute barring American companies from bribing foreign officials); and pursuing huge changes in policy (as on tariffs and immigration) through emergency orders rather than legislation.

He’s asserted absolute control over the executive branch through mass layoffs; an erosion of civil service protections for federal workers; the wholesale dismissal of inspectors general; and the firing of commissioners at independent regulatory agencies (a move that doubles as an assault on the authority of Congress, which structured those agencies to insulate them from direct presidential control).

He’s arguably already crossed the line into open defiance of lower federal courts through his resistance to orders to restore government grants and spending, and his refusal to pursue the release of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the undocumented immigrant the administration has acknowledged was wrongly deported to El Salvador. And while Trump so far has stopped short of directly flouting a Supreme Court order, no one could say he’s done much to follow its command to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s return.

Trump has trampled traditional notions of federalism (especially as championed by conservatives) by systematically attempting to impose red state priorities, particularly on cultural issues, onto blue states. His administration has arrested a judge in Wisconsin and a mayor in New Jersey over immigration-related disputes. (Last week, the administration dropped the case against the Newark mayor and instead filed an assault charge against Democratic US Rep. LaMonica McIver.)

Most unprecedented have been Trump’s actions to pressure civil society. He has sought to punish law firms who have represented Democrats or other causes he dislikes; cut off federal research grants and threatened the tax exempt status of universities that pursue policies he opposes; directed the Justice Department to investigate ActBlue, the principal grassroots fundraising arm for Democrats, and even ordered the DOJ to investigate individual critics from his first term. Courts have already rejected some of these actions as violations of such basic constitutional rights as free speech and due process.

It’s difficult to imagine almost any previous president doing any of those things, much less all of them. “This ability to just deter other actors from exercising their core rights and responsibilities at this kind of scope is something we haven’t had before,” said Eric Schickler, co-author with Pierson of the 2024 book “Partisan Nation” and also a UC Berkeley political scientist.

For Trump’s supporters, the breadth of this campaign against the separation of powers is a feature, not a bug. Russell Vought, director of the Office of Management and Budget and one of the principal intellectual architects of Trump’s second term, has argued that centralizing more power in the presidency will actually restore the Constitution’s vision of checks and balances.

In Vought’s telling, liberals “radically perverted” the founders’ plan by diminishing both the president and Congress to shift influence toward “all-empowered career ‘experts’” in federal agencies. To restore proper balance to the system, Vought argued, “The Right needs to” unshackle the presidency by “throw(ing) off the precedents and legal paradigms that have wrongly developed over the last two hundred years.”

Trump summarized this view more succinctly during his first term, when he memorably declared, “I have an Article II (of the Constitution), where I have to the right to do whatever I want as president.”

Whatever else can be said about the first months of Trump’s second term, no one would accuse him of faltering in that belief.

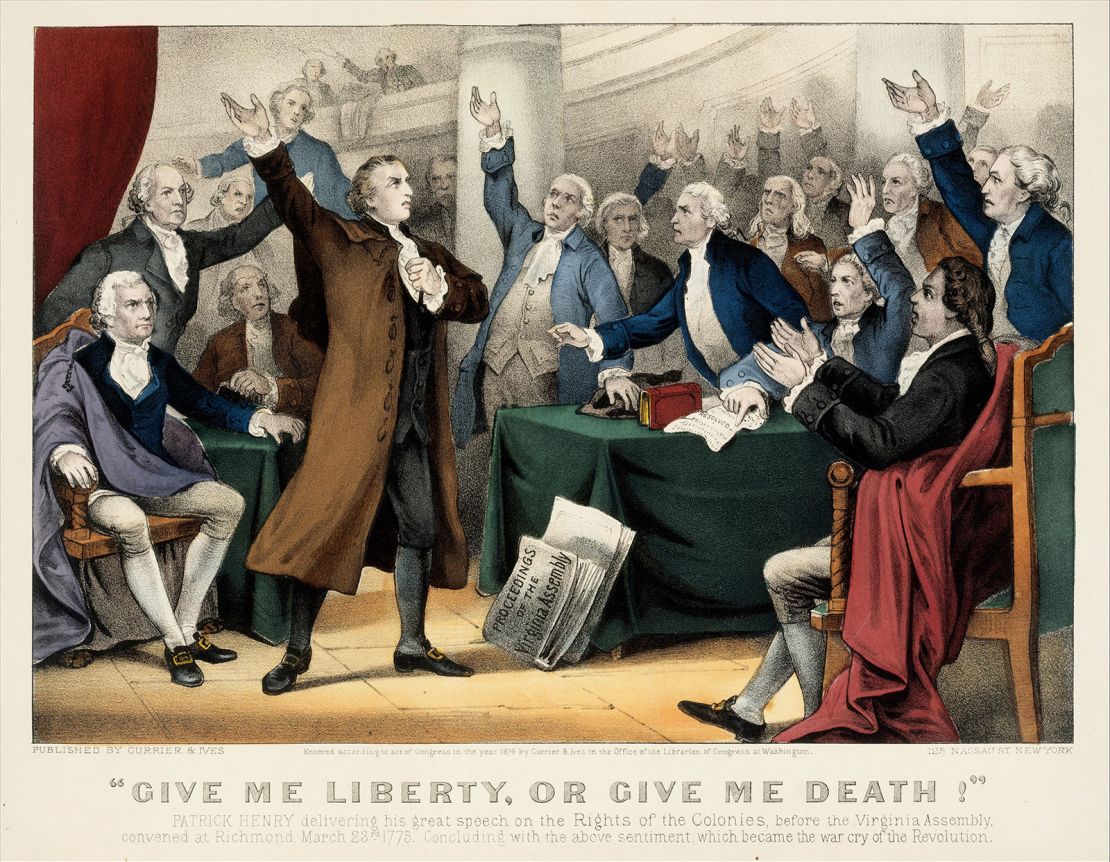

Earlier this year, Trump signed a proclamation honoring the 250th anniversary of the famous “give me liberty or give me death” speech by Patrick Henry, the Revolutionary War era political leader.

Trump’s proclamation did not note the speech Henry delivered 13 years later to the Virginia convention considering whether to endorse the newly drafted US Constitution. Henry opposed ratification, mostly because he believed the Constitution provided too little protection against a malign or corrupt president.

“If your American chief, be a man of ambition, and abilities, how easy is it for him to render himself absolute!” Henry declared. If a president sought to misuse the vast authorities placed at his disposal, Henry warned, “what have you to oppose this force? What will then become of you and your rights? Will not absolute despotism ensue?”

Brown University political scientist Corey Brettschneider, who highlighted that speech in his recent book “The Presidents and the People,” wrote that Henry was among the founders who most clearly recognized that the “presidency was a loaded gun and its ostensibly benign powers might be used for ill.”

Even those who supported the Constitution shared some of Henry’s misgivings. Preventing a descent into tyranny was a major theme throughout the Federalist Papers, the essays written primarily by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton to encourage states to adopt the Constitution.

To Madison, one of the document’s chief virtues was that it divided power in a manner that made it difficult for any single individual or political faction to assume absolute power. A core idea in the Constitution’s design was that executive, legislative and judicial branch officials would zealously guard the prerogatives of their institution and push back when either of the others encroached on it. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” Madison wrote in one of the Federalist Papers’ most famous sentences. “The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.”

Madison thought the Constitution created a second line of defense against despotism. Not only would power be diffused across the three branches of the federal government, it would also be apportioned “between two distinct governments” at the national and state level. That federalism would create what Madison called “a double security (for) the rights of the people.”

The Constitution always had faults, most glaringly its tolerance of slavery. And its protections wobbled and cracked at times when presidents threatened basic rights – often in, or immediately after, war time.

But as Pierson and Schickler argued in “Partisan Nation,” the separation of powers generally worked as intended through most of US history. “For almost a quarter of a millennium,” they wrote, “the operation of American government tended to frustrate the efforts of a particular coalition or individual to consolidate power, dispersing political authority and encouraging pluralism.”

The founders’ strategy, though, was showing signs of strain even before Trump emerged as a national figure. In recent decades, Pierson and Schickler argue, the increasingly polarized and nationalized nature of our political parties has attenuated the Constitution’s system of checks and balances and separation of powers (a structure often described as the Madisonian system). While Madison and his contemporaries thought that other officials would focus primarily on defending their institutional prerogatives, in modern politics, state and federal officials, and even judicial appointees, appear to prioritize their partisan identity on the Democratic or Republican team.

That’s steadily diminished the willingness of other power centers to push back in the way Madison expected against a president from their own side overstepping his boundaries. Trump is both building on that process and escalating it to an entirely new level of ambition.

Will Trump succeed in overwhelming the separation of powers and concentrating power in the presidency – potentially to the point of undermining American freedom and democracy itself?

Even to pose those questions is to contemplate possibilities that Americans have rarely needed to imagine.

Brettschneider’s book traces the history of public resistance to presidents who threatened civil liberties and the rule of law, including John Adams, Andrew Johnson and Richard Nixon. He says those precedents offer reason for optimism, but not excessive confidence, that the system will survive Trump’s offensive. “We have these past victories to draw on,” Brettschneider said. “But we shouldn’t be naïve: The system is fragile. We just don’t know if American democracy will survive.”

Levin, the author of “American Covenant,” an insightful 2024 book on the Constitution, doesn’t see Trump presenting such an existential challenge. He agrees Congress is unlikely to muster much resistance to Trump’s claims of unbounded authority: “The weakness of Congress, and the vacuum that weakness creates, is the deepest challenge confronting our constitutional system, even now,” Levin wrote. But he believes the Supreme Court ultimately will constrain Trump.

Levin believes the court will distinguish between what he calls the “unitary executive” theory – which posits the president should exert more authority over the executive branch – and the “unitary government” theory, which would expand the president’s power over other branches and civil society. “So this court will simultaneously strengthen the president’s command of the executive branch … and restrain the president’s attempts to violate the separation of powers,” Levin predicts. That expectation underpins his belief that Trump’s power grabs ultimately are more likely to weaken than strengthen the presidency.

Analysts to Levin’s left are much less confident the same Republican-appointed Supreme Court majority that voted to virtually immunize Trump from criminal prosecution for official actions will consistently restrain him – or that it is guaranteed Trump will comply if it does. They tend to see Trump’s second term as presenting an almost unparalleled stress test for the Constitution’s interlocked mechanisms to preserve freedom and democracy.

The fact that the Madisonian system of checks and balances, separation of powers and federalism has “sustained itself for 235 years can give you a lot of confidence” that it will endure, Schickler said. “What I would say is: We shouldn’t be too confident. It broke once before in the Civil War. It’s not going to break in the same way, but the possibility of it breaking is real.”

The first months of Trump’s return have revealed his determination to shatter the defenses that system has constructed against the misuse of presidential power. Less certain is whether officials from the other branches of government, leaders in civil society, and even ordinary Americans, will show the same determination to defend them.