At the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, European leaders signaled an ambitious new intent to play a bigger role in Indo-Pacific affairs.

French President Emmanuel Macron called for a “strategic balance” in Asia, while European Commission Vice President Kaja Kallas described Europe as a “partner, not a power.”

Officials from Germany, Sweden, and Finland echoed these views. The proposition is that Europe could serve as a stabilizing third pole, positioned between China’s assertiveness and the United States’ fluctuating and uncertain commitments.

This framing has intuitive appeal. Europe is viewed as technologically capable, geopolitically distant and less hegemonic than either the US or China. Yet the Indo-Pacific remains a maritime-first theater, where strategic relevance is defined not by sentiment but by presence and sustained investment.

European strategic limits

The Indo-Pacific region accounts for over 60% of global maritime trade and encompasses some of the world’s most contested flashpoints, including the South China Sea, the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

China now fields the world’s largest navy, with 355 ships in 2025 and a projected 440 by 2030. The US retains dominance in tonnage and strike capability but is capable of building only 1.5 ships annually, compared to China’s at least eight.

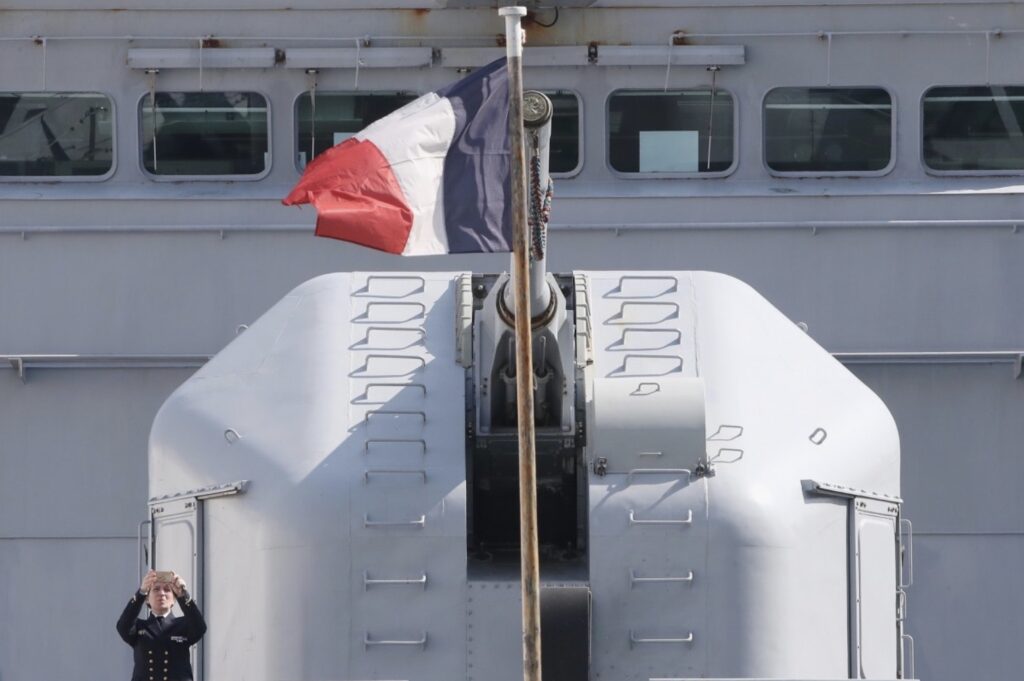

By contrast, European capabilities remain insufficient for sustained operations in the Indo-Pacific. Only France, the United Kingdom and Italy operate aircraft carriers. The UK has two Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, but only one is deployable at a time due to maintenance cycles.

As of 2025, the UK’s Royal Navy fields just 16 operational F-35Bs, well short of the 24 typically required for a full carrier air wing. France’s sole carrier, the Charles de Gaulle, when docked, removes its carrier-based airpower from the theater. Italy’s Cavour and Trieste remains reliant on AV-8B Harriers, with fewer than 10 next-generation aircraft available as of 2024.

All three navies face shortfalls in escorts and support vessels. While a US carrier strike group typically includes four to six escorts and one to two support ships, European deployments often manage only two to three escorts. It is therefore unsurprising that less than 5% of Europe’s naval assets are deployed to the Indo-Pacific.

Indo-Pacific opportunities for Europe

Europe’s current naval presence may be limited but three avenues offer Europe the opportunity to make meaningful, near-term contributions to Indo-Pacific security.

First, Europe could pursue full membership in the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus), the region’s foremost multilateral security forum.

Established in 2010, ADMM-Plus comprises ASEAN and eight dialogue partners: The United States, China, Japan, India, Australia, Russia, New Zealand, and South Korea. The forum has conducted more than 20 joint exercises and supports expert working groups in areas such as maritime security, counterterrorism and cyber defense.

However, bloc cleavages are deepening. Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea are much more dependent on US defense systems, while Russia, in the aftermath of its war in Ukraine, is increasingly dependent on China.

ADMM-Plus may be due for a strategic evolution, one in which Europe could act as a stabilizing third pillar of Indo-Pacific security.

Europe’s full membership as dialogue partners would enable it to contribute meaningfully to regional capacity-building, particularly in maritime domain awareness, counter-piracy and cybersecurity, areas where it possesses deep technical expertise.

Second, Europe can increase its strategic relevance in the region by linking defense exports to local industrial development. Southeast Asian states increasingly expect arms deals to include technology transfers, job creation and long-term economic value. This was reflected in ASEAN chairman Anwar Ibrahim’s SLD25 statement that “trade is part of our strategic architecture.”

Recent European defense deals have embraced this logic. Sweden’s Gripen sale to Thailand included training and maintenance infrastructure. France’s 7.5 billion euro (US$8.6 billion) Rafale agreement with Indonesia and Germany’s 1.2 billion euro submarine contract with Singapore similarly offered industrial participation.

To move beyond fragmented, bilateral arrangements, however, the EU should use instruments such as the European Peace Facility (EPF) and Security Action for Europe (SAFE), a 150 billion euro defense investment fund approved in May 2025. These mechanisms can support coproduction, joint ventures and localized assembly aligned with both European supply chain interests and Southeast Asia’s development needs.

Finally, programs like SAFE are designed to strengthen Europe’s defense industrial base by financing large-scale joint procurement and infrastructure.

But scaling this capacity cost-effectively may require trusted partnerships beyond Europe’s borders. ASEAN offers that potential, particularly if it is more closely integrated into European defense supply chains.

Security supply chains

If structured to meet SAFE’s eligibility criteria – such as majority EU ownership or controlled IP – these arrangements could support the program’s objectives of efficiency, resilience and industrial depth while enabling Southeast Asian states to modernize affordably under transparent, rules-based frameworks.

All in all, Europe’s growing Indo-Pacific aspirations are diplomatically significant but strategically incomplete. To play a central role, Europe needs to embed itself in regional institutions such as ADMM-Plus, align defense engagement with economic development and integrate trusted regional partners into its defense industrial supply chains.

These moves won’t match American force projection or offset Chinese naval expansion, but they could anchor Europe as a durable, strategic partner in a region looking for options beyond the familiar two superpower poles.

Marcus Loh is chairman of the Public Affairs Group at the Public Relations and Communications Association (PRCA) Asia Pacific. He also serves on the executive committee of SGTech’s Digital Transformation Chapter, contributing to national conversations on AI, data infrastructure, and digital policy.

A former president of the Institute of Public Relations of Singapore, Loh has played a longstanding role in shaping the relevance of strategic communication and public affairs in an evolving policy, technology and geoeconomic landscape.