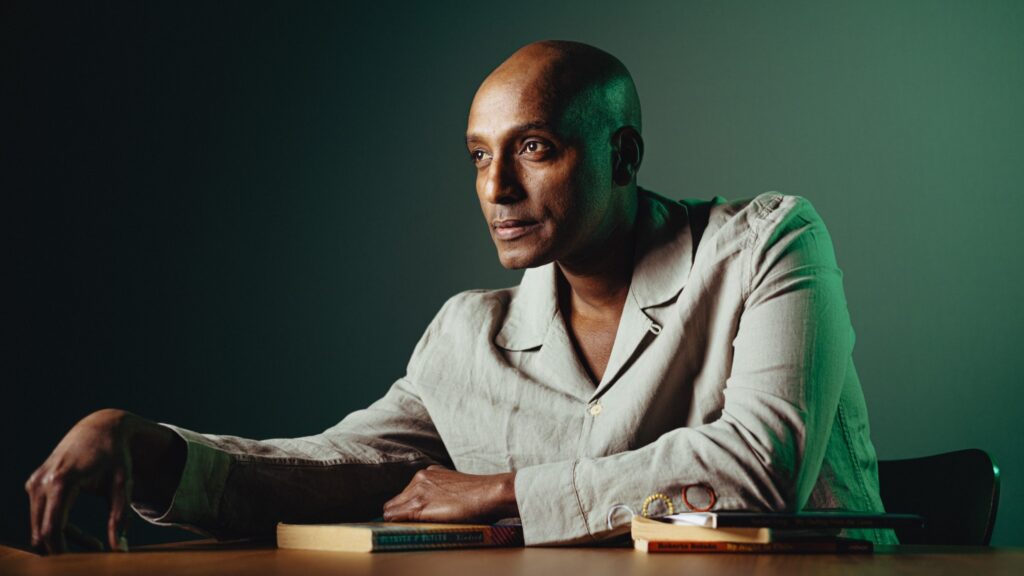

Sulaiman Addonia is an Eritrean-Ethiopian novelist who lives in Brussels. His most recent novel, The Seers (2024), unspools in a single, 136-page paragraph, exploring the world of Hannah, an Eritrean refugee in London, and the redemptive power of art.

It’s familiar territory for the author: Addonia and his brother claimed asylum as unaccompanied minors in the city in 1990.

When he arrived in England as a child, he spoke no English, however, he went on to gain an Economics degree, and then an MA in Development Studies from SOAS.

Addonia’s second novel, Silence is My Mother Tongue (2019), is set in a refugee camp in Sudan; the author spent his early years in a Sudanese refugee camp after his village in Eritrea was subject to a massacre by the Derg regime during the Eritrean war of independence, and his father was murdered.

As a teenager, the author lived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where his mother worked as a domestic servant, and the city forms the backdrop of his debut novel, The Consequences of Love (2008), which was longlisted for the 2019 Orwell Prize.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In Brussels, in 2019, he founded the Creative Writing Academy for Refugees & Asylum Seekers and the Asmara-Addis Literary Festival in Exile (AALFIE), which runs biannually.

In 2022, AALFIE was recognised as one of the top literary festivals in the world.

How has the refugee experience informed your writing?

Everything becomes an input, I guess. All my life I’ve been moving around, being forcibly displaced. And when you write from the subconscious, as I tend to do, then without you knowing, your imagination tends to pick and choose those things that are interesting to explore.

I was an economist before I became a writer, and even then, I was preoccupied with themes such as poverty and displacement.

Those [experiences] gave me a lot of pain but they also led me to places and experiences I otherwise might not have had.

They’re part of my existence, and they formed most of the things I tended to ask questions about. I think the novel is all about trying to answer those questions.

In The Seers, the protagonist Hannah inhabits the shadowlands of the city, as she tries to negotiate life in London as a refugee, is this something you experienced?

I experienced the loneliness that Hannah feels, but how she deals with it and how I deal with it are quite different, obviously.

[With Hannah], I was trying to show how you react to loneliness. How do you react to being cast aside? How do you react to being on your own in a country that you are not really part of?

What astonished me about Hannah is that when she is told you can’t study, you can’t do any job, you basically have to stay in a room; instead of feeling sorry for herself, she uses that time to go on an interior journey, where she discovers a rich language… and that’s the language of love, intimacy and experimentation.

She’s saying I’m going to be basically my own country, my own city, my own language.

You wrote The Seers on your mobile in three weeks in front of the Ixelles ponds in Brussels?

Moving from London to Brussels [in 2009] was the only time I moved out of choice because I fell in love with a Belgian woman, so it was the first time I displaced myself by myself.

My partner had her friends, her family, then she found a full-time job and I became lonely.

I’ve always been a flaneur, but in Brussels, it stepped up a bit. One of the things that saved me at the time was walking.

‘I remember coming to the UK and having all these stories, all these traumas, and not even having a place to go and talk or even go and write if I wanted to’

– Sulaiman Addonia, novelist

My favourite poet Lorca says: “I lost myself in order to find the light burning within,” and that really happened to me.

I disappeared into my own world and I found friendship with avant-garde artists and they started to reshape my imagination.

I became fascinated with this idea of writing from the subconscious and accepting what’s given to you by your imagination.

It was a beautiful day in March 2020, and the city was in lockdown. I stood in front of the ponds and the name came to me – Hannah – and then I just took out my iPhone and followed her.

Three weeks later, I had a complete novel, but it was so intense. Hannah took me on this kind of trip, really exciting, like being in a fast lane.

I absolutely loved it. I felt sick after I finished that book because I felt like I was writing on the edge. There was a lot of pain.

The loneliness you experienced in Brussels was formative.

In Brussels, it was a different terrain, different languages, everything. [Previous to that] I had been head down working, and that’s what a lot of immigrants do, you know? Sometimes you don’t have the chance to sit with yourself and say, “I’ve been through that.” And then I was by myself and… this child, this years of being in a refugee camp, the whole massacre thing… everything started to happen.

I didn’t know what to do with it. And yes, it was very difficult, but I think it was necessary as well. It was one of the most painful experiences of my life going to Brussels, but as a writer, it’s completely changed me.

We’re meeting at the London Library. What did libraries mean for you as a child refugee in London?

A lot. When I came to this country, I was given £17 a week to use for transport, to eat, buy medicine, etc; it’s nothing, so I would not have become a storyteller without going to a library because how would you buy books, it’s impossible.

You speak about your mother being one of your key literary influences. Can you tell me more?

When I was about three, she left for Saudi Arabia [to work as a domestic servant for a Saudi princess]. I stayed behind with my grandmother and siblings in a refugee camp.

The usual thing for women is to dictate letters to a male writer, but she decided to record herself [on these cassette tapes]. They would arrive with migrant workers who had travelled from Jeddah to Khartoum before arriving at our remote camp.

Looking back, I’m always interested in people who subvert the system, who actually take power, especially when it comes to storytelling. She would not just ask us how we were; she would sing, improvise and describe the palace that she was living in at the time.

So when I finally joined her, six or seven years later, I was astonished at how her descriptions were quite accurate when it came to the environment, and that’s the power she had as a storyteller. People say that my writing is descriptive and I am sure that ability comes from her.

You spent your early teens in Jeddah when your mother was working there as a domestic servant. Was it there that you developed your love of literature?

It was through my elder brother actually. He came to read when he lost his hearing. We are best friends; he is two years older than me.

He used to be very social and I was the introvert. He lost his hearing overnight from meningitis and in the refugee camp, there was no clinic, no nothing.

Memories of displacement: Sudanese poet K. Eltinae on writing ‘verses in the sky’

Read More »

He didn’t have a hearing aid or anything like that, so I used to be the one to translate the world into his ear. And at the camp, people would come from the city with old, expired newspapers and he started reading.

He became obsessed with reading, and the world of literature and books became his way of communicating, and he shared that love with me.

He befriended a Sudanese intellectual who introduced him to books, which were smuggled at the time, such as Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North, really hardcore books, which I shouldn’t have read at my age.

Your debut novel, The Consequences of Love, is about the life of young lovers under the strict Wahhabism of Saudi state rule. What compelled you to write this book about Saudi society?

It’s based on a true story. In the ’80s when I was in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia was, and still is, a gender-segregated society. Women are mostly in the black veil and boys can wear what they want.

When I was at school there, we used to see some of the girls dropping a note at the boys’ feet and those were the boys that they liked.

So it was subversive – this idea of love that would not have happened without these girls taking the risk.

So I started the novel with that: this idea of being guided by love, being guided by desire, even if you are living in an oppressive system, and I built a world around it.

You spoke about the Anglo-Saxon literary tradition as having rules like chains binding you to a strict interpretation of a novel. What do you mean by that?

There is this prevailing idea of what a novel is about and how you have to perform within this frame for you to attain success. I’ve lived in oppressive states and the last thing I want to do is curtail my imagination.

My background is oral storytelling. The Arabic way of storytelling is completely different to the English way. In the refugee camp, we didn’t have books but we’d watch plays being performed or dancing, and so there are a lot of influences outside the novel that shaped my imagination.

I wanted to be faithful to that, and to give power to this imagination that has been through different continents, different cultures, different languages. For me, it’s all about freedom, giving the imagination the freedom it needs to perform, and then it’s about defending your book.

I come from people who are all about defending the thing they love, like my mum. When bombs were being dropped on our place back home, she sheltered me with her body. Once you love something, you really have to defend it with all you have.

Your mother sent you and your brother unaccompanied to England because she was worried you were going to be deported back to a war zone. How did you settle in the UK?

We always talk about people who don’t want immigrants, but we never actually talk about people who welcome immigrants.

It’s important for me not just to talk about the people who didn’t want me here, but those people who actually went out of their way to help me.

My brother had a social worker, a British-Caribbean lady, who helped us, and there was an English lady as well.

I really appreciate those people that ran a day centre for refugees, where [we were offered] just simple things, friendship, being offered tea and a biscuit and I think it’s important to acknowledge that.

How did the Creative Writing Academy for Asylum Seekers & Refugees come about?

I’ve never been afraid of failure because my entire existence is based on taking risk, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. Art and literature has always been a constant, the part that really gave me a sense of what life is all about.

I remember coming to the UK and having all these stories, all these traumas, and not even having a place to go and talk or even go and write if I wanted to.

I felt I could maybe create a space where newcomers to Europe could come to that space: they could just sit there in silence, or if they had stories they wanted to write about, then I or my friends could actually support them with what we know about storytelling.

‘Part of what motivated me to found the festival was frustration. I would be invited to talk at literary festivals and always asked about the refugee experience, and while I think it’s important, there’s another side to me as an artist’

– Sulaiman Addonia, novelist

Because being a refugee isn’t just about [basic needs,] eating, being given clothes or a home, it’s also about [satisfying] your intellect, who you are as a person, what you want to achieve. And that’s how the idea of the creative writing academy started.

At the moment, we have the library in Ixelles that gives us a space to work and Passa Porta, the international house of literature.

We work with about 10-12 students and our tutors are multilingual so it’s an inclusive space.

So many people started to come, the academy just went from strength to strength. I remember a Yemeni student saying: “Outside this classroom I am a refugee; but here I am a writer.”

At the same time, the idea came to me to have a literary festival. Brussels is the second most diverse city in the world after Dubai, but when you go to the main cultural institutions, the main languages spoken are English, Dutch, French, and I thought what a shame that we have all these languages that are not spoken [in main settings].

So we have the literary festival which is multilingual and our students perform there [poetry, prose, dance] following their two-week masterclass.

We put them in touch with established artists, so they work with them and it’s an amazing opportunity for them to perform publicly as well.

Part of what motivated me to found the festival was frustration. I would be invited to talk at literary festivals and always asked about the refugee experience, and while I think it’s important, there’s another side to me as an artist as well.

I don’t want to be pigeonholed or confined to one thing. Last year’s festival’s theme was “The Body’s Languages” and we had writers from 38 countries.

We don’t translate – it’s all about feeling the performance. Refugees are always expected to assimilate, but sometimes we have to be seen with everything – our food, experiences, religion and languages.

You’ve given so much of yourself to the community when you yourself have been through a lot. Where does that drive come from?

The [refugee] day centre in London left a big mark on me. I know the value of people coming together to support each other, especially at times when things are very difficult.

There are a series of people who’ve sacrificed so much for me to be here, I can’t ignore that. If there’s something I can do [to give back], I will do it.

Sulaiman Addonia was in London for the Preserving Culture in Conflict event at the London Library on 5 June in the lead-up to Refugee Week. He was in conversation with Sudanese author and activist Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Ukrainian writer, historian and director of the Ukrainian Institute in London, Dr Olesya Khromeychuk and Palestinian author Ahmed Alnaouq.