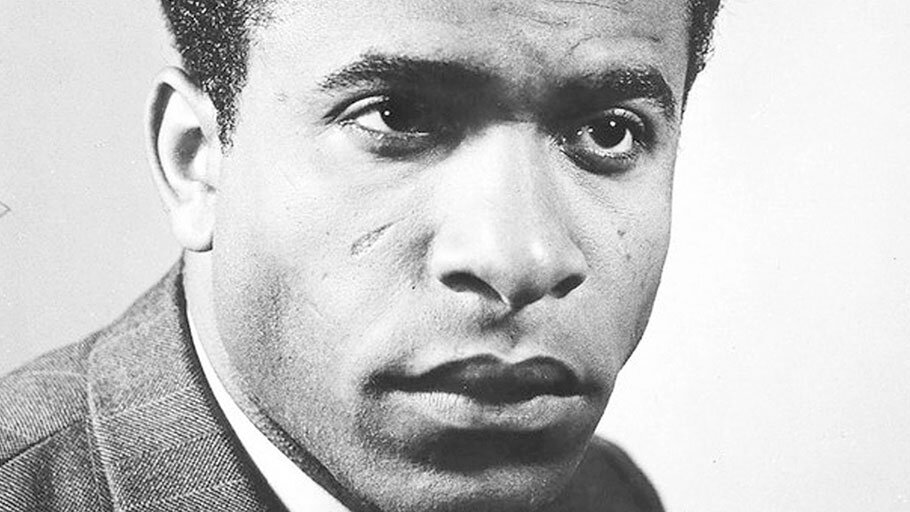

Adam Shatz’s new book is a masterful tribute to one of the 20th century’s most influential anti-colonial thinkers.

Written with intellectual richness and narrative verve, his biography of Frantz Fanon brims with historical depth and contemporary resonance.

From its opening pages, the book captivates with vivid storytelling: we meet Fanon in November 1960, travelling under a Libyan alias across the Sahara as part of an FLN commando unit.

Shatz describes the scene with cinematic detail as Fanon marvels at desert sunsets and senses history in motion.

In his travel journal, Fanon observes that “This part of the Sahara is not monotonous” and exults: “A continent is on the move and Europe is languorously asleep”, even as he warns that “the spectre of the West” remains “everywhere present and active”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Such passages illustrate Shatz’s narrative style: elegant and evocative, seamlessly blending Fanon’s own voice with a historian’s eye for context.

The result is a biography that reads at times like a novel yet never sacrifices analytical depth.

The Rebel’s Clinic provides a thorough exploration of Fanon’s brief but impactful life, shedding light on the many sides of the man often mythologised solely as a fiery revolutionary.

The life and times of a revolutionary

Shatz restores Fanon in full, not just as the author of The Wretched of the Earth, known for advocating anti-colonial violence, but also the practising psychiatrist, devoted son and husband, and an “expansive humanist” grappling with the psychological effects of racism.

The book is organised both chronologically and thematically, tracing Fanon from his Caribbean upbringing in Martinique, through his wartime service and existential awakening in France, to his radicalisation in Algeria, and finally to his pan-African commitments in the last year of his life.

In these sections, Shatz places Fanon’s personal journey within the broader movements of mid-20th-century liberation struggles – from the decline of French colonialism in north Africa to the chaos of Cold War politics in newly independent African countries.

The Rebel’s Clinic, even when it doesn’t fully cater to the radical interpretations of Fanon, still howls with defiance

The narrative is rich with well-researched details. We see Fanon treating patients in an Algerian psychiatric ward in Blida even as he secretly supports the FLN; we follow him to Accra and Leopoldville, navigating the complex politics of pan-African conferences alongside figures like Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba.

Shatz pays close attention to the contradictions and challenges Fanon encountered. For example, he discusses Fanon’s uneasy role as an FLN envoy who, for geopolitical reasons, advised Lumumba to step aside during the Congo Crisis, a sobering example of how a dedicated intellectual could be limited by the very revolution he championed.

These episodes, shown with nuance, add depth to the book and prevent any simplified, hagiographic portrayal of Fanon.

Crucially, Shatz brings out Fanon’s passionate voice and evolving ideas in tandem with these life events. We witness the creation of Black Skin, White Masks (1952) as Fanon grapples with the inferiority complex instilled by colonial racism and delves into the existential dimensions of Black consciousness.

We then trace the sharpening of his thought in A Dying Colonialism (1959) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), as experience in the Algerian war leads Fanon to champion revolutionary violence as a means of psychic and social transformation.

Shatz shows how Fanon’s psychiatric training and readings in phenomenology informed his insights into the “racialised unconscious,” or how his dialogues with contemporaries, such as Aime Cesaire, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, helped shape his philosophies of liberation.

The biography’s intellectual richness lies in this ability to trace lineages of thought: Shatz presents Fanon not as an isolated prophet but as a thinker in conversation with both Black radicalism and dissident European left traditions.

At the same time, Shatz keeps Fanon’s humanity in view. Amid discussions of guerrilla strategy and trauma, we get delightful glimpses of Fanon’s everyday life and personality.

He constantly reminds us that Fanon was not all polemics and manifestos, he was also a man who enjoyed good food, music, and friendship.

Stylistically, The Rebel’s Clinic balances scholarly rigour with accessible prose. Shatz is an essayist of considerable literary skill, and it shows: the prose is at once erudite and engaging.

Complex theoretical concepts like “the dream life of race and oppression,” or the psychosocial effects of colonial violence, are explained with clarity, never devolving into jargon.

When Shatz does quote from Fanon’s sometimes dense texts, he provides context so that general readers can appreciate the meaning. This makes the biography inviting to non-specialists, while remaining deeply informative for those already familiar with Fanon’s work.

Gaza, genocide and revolutionary violence

One of the most striking features of The Rebel’s Clinic is its timeliness. Shatz completed the book in 2022, but an epilogue titled “Spectres of Fanon” brings Fanon’s legacy squarely into the present, specifically, into the context of the Gaza War that erupted in October 2023.

In these final pages, Shatz engages directly with the ongoing Palestinian struggle and Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, using Fanon’s framework to analyse the events.

The result is a bold and provocative coda that has naturally stirred debate.

Shatz draws a pointed parallel between France’s brutal counterinsurgency in 1950s Algeria and Israel’s response to the surprise attack of October 2023 by the Palestinian resistance.

Israel’s campaign, Shatz notes, “followed the French army’s playbook” from Algeria. The Israeli army unleashed “mass bombardment, ethnic cleansing, and starvation” in Gaza, actions that amounted to genocide.

The rhetoric of Israeli officials, too, echoed the dehumanising language of colonial warfare.

Shatz cites Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant’s declaration that “We are fighting human animals,” noting how chillingly it confirmed Fanon’s observation that “when the colonist speaks of the colonised, he uses zoological terms,” reducing the oppressed to a “bestiary” of subhumans.

Shatz is unsparing in condemning this brutality. His language in the epilogue, while measured, carries a moral urgency; one can sense his outrage at what he describes as Israel’s campaign of collective punishment.

Indeed, Shatz aligns with those international voices who have labelled the assault on Gaza a genocide.

Israel-Palestine war: ‘We are fighting human animals’, Israeli defence minister says

Read More »

He reminds readers that countries with histories of colonisation, like post-apartheid South Africa, have formally charged Israel with genocide at the International Court of Justice.

Meanwhile, Western political establishments, so quick to invoke moral principles in other conflicts, have “done little to end Israel’s slaughter, when [they haven’t] been moved to defend it”.

In Shatz’s framing, the Gaza War has revealed a world order “cut in two,” much like Fanon described during the Algerian War. On one side, colonised peoples and their allies demanding justice; on the other, imperial powers and their apologists justifying colonial atrocities in the name of security.

By invoking this Fanonian image of a “world cut in two,” Shatz underscores how little has changed in the fundamental dynamics of oppression and solidarity.

Yet Shatz does more than castigate Israeli colonial violence. He also tackles a thornier question, one that has provoked intense debate amongst readers and activists: How should we view the violence of the colonised in this conflict?

What would Fanon do?

The 7 October Hamas-led attack, which killed both soldiers and hundreds of non-combatants from the settler colonial society and took others hostage, immediately raised Fanon’s spectre in global discourse.

Shatz notes that pro-Palestinian voices, especially on the radical left, were quick to cite Fanon in defence of the military assault.

In their reading, Hamas’s attack was pure Fanon: an explosion of righteous vengeance by the wretched of the earth, giving the coloniser a taste of his own medicine.

Conversely, Fanon’s detractors have seized on the same events to paint him as an avatar of indiscriminate violence, accusing anyone condoning the killings (even passively) of being in thrall to Fanon’s dangerous ideas.

Fanon saw armed struggle as a necessary catharsis for colonised peoples

Amid this polarised invocation of Fanon, Shatz poses the uncomfortable question outright: Would Fanon have endorsed the 7 October attack?

Shatz’s answer is two-fold.

On one hand, he acknowledges that much of what transpired fits the pattern of anti-colonial violence, which Fanon famously defended.

Fanon saw armed struggle as a necessary catharsis for colonised peoples. By that logic, Shatz suggests, the initial phase of “Al-Aqsa Flood” operation, the assault on military targets, might well have met with Fanon’s approval.

Moreover, as a psychiatrist, Fanon would readily “understand why Palestinians took up arms” after decades of having their land stolen, their borders sealed, and their families bombed with impunity.

In Fanon’s own words, which Shatz cites, it was “logical” that “the very same people who had it constantly drummed into them that the only language they understood was that of force, now decide to express themselves by force”.

Even the gruesome celebratory aspect, the fact that some Palestinians exulted in an attack that killed non-combatants, would not have surprised Fanon, Shatz notes.

In the zero-sum moral universe of a colonial war, Fanon wrote, “good is simply what hurts them most”. The oppressed may invert the coloniser’s own values, coming to see their enemy’s suffering as their own reward.

All of these points demonstrate Shatz utilising Fanon’s psychological and political insights to contextualise the rage underlying the revolt in Gaza. He refuses to join the chorus that simplistically demonises Palestinian resistance as “terrorism” divorced from context.

Instead, Shatz validates the root causes and the emotional logic of the uprising: decades of humiliation made the eruption of violence inevitable, even “logical”.

In this regard, he stands firmly in the anti-colonial camp, underscoring the justice of the Palestinian struggle and the profound culpability of the Israeli state for creating the powder keg that finally blew.

No ‘uncritical cheerleader’ for bloodshed

On the other hand, Shatz pointedly refuses to endorse all aspects of the 7 October attack fully.

Here is where his approach has drawn some anger from more radical quarters. Invoking Fanon’s own view of violence, Shatz argues that Fanon “did not regard all forms of anti-colonial violence as equally legitimate”.

Fanon, contrary to his caricature, was not an uncritical cheerleader for bloodshed.

The Zone of Interest: The banal dreams of Nazi settler colonialism

Read More »

In fact, he criticised FLN fighters who committed wanton atrocities, describing their cruelty as “the almost physiological brutality that centuries of oppression nourish and give rise to”.

And in an often-overlooked passage of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon warned that “racism, hatred, and the ‘legitimate desire for revenge’ alone cannot nurture a war of liberation”.

Hatred may ignite the first flames of revolt, “these flashes of consciousness which fling the body into a zone of turbulence,” but “if it is left to feed on itself,” Fanon cautioned, it disintegrates and loses direction.

Put more bluntly, “hatred is not an agenda”.

Shatz foregrounds this to argue that while the initial military strike might be justified as resistance, the deliberate “murder of concertgoers and kibbutz dwellers,” as he describes it, is harder to defend as acts of liberation.

Shatz implies that Fanon himself would have recoiled at certain excesses.

The role of mobilisation

He further concludes that the true “Fanonian” breakthrough of our time may lie not in militant violence, but in solidarity and mass mobilisation.

In a surprisingly hopeful turn, he observes the worldwide outrage and protest that the Gaza war has galvanised.

“If there has been a Fanonian ‘leap of invention’ since October 7,” Shatz writes, “it is… the emergence of a broad-based, international movement for Palestinian freedom, launched by students of every racial group and every faith.”

Across university campuses and city streets, young people of diverse backgrounds have rallied to demand an end to the slaughter in Gaza and an end to institutional complicity in oppression.

“We are all Palestinians,” they chant in a spirit of intersectional solidarity that, however idealistic, Fanon might have appreciated.

Shatz describes visiting a student encampment at Bard College (where he teaches) and seeing more than one student reading The Wretched of the Earth.

This anecdote serves as a touching bookend: Fanon’s words, six decades old, are inspiring a new generation who face a different empire but the same fundamental struggle for human dignity.

Shatz muses about what lessons these students draw from Fanon and whether Fanon would be gratified or dismayed to still be so relevant.

The epilogue ends on a poignant note, with the author suggesting that Fanon likely hoped his work would not remain timeless, that its relevance would expire with the end of colonial oppression.

Liberal moralising?

Shatz’s handling of the Gaza war and the question of violence has not pleased everyone.

From the viewpoint of some revolutionaries, Shatz’s critique might look like a form of hesitation or equivocation in a moment that, to them, demands unwavering partisanship.

After all, if one truly recognises that Gaza is the site of a one-sided genocide, any focus on the misdeeds of the oppressed can seem like a dangerous distraction.

Shatz’s detractors in these circles would argue that highlighting Palestinian “transgressions” (even with ample context and empathy) plays into a false “both-sides” narrative, one that the mainstream media often uses to equate the violence of the oppressor and the oppressed.

They fear that criticisms of the 7 October attack or Hamas give fodder to defenders of Israel’s aggression: Why dwell on the crimes of the powerless, they ask, when the far greater crime is being perpetrated by a nuclear-armed state raining bombs on civilians?

Some also sense a paternalistic undertone when outside commentators, especially Western intellectuals, lecture occupied people on how to conduct their resistance.

Fanon himself spoke scathingly of those who preach non-violence to the oppressed while enjoying the fruits of colonial violence.

To these critics, Shatz’s critique of certain Hamas actions, even as he simultaneously decries Israel’s brutality, might appear as a betrayal of revolutionary solidarity, an instance of liberal moralising amid a struggle that brooks no neutrality.

On the other side, more conservative observers might bristle at Shatz’s willingness to contextualise, if not quite justify, violence against Israelis.

They might accuse him of excusing “terror” by invoking historical oppression.

Shatz occupies a middle ground that is frankly a difficult place to be. In straddling this line, he highlights a tension inherent in Fanon’s legacy and in anti-imperialist thought more broadly: the tension between an uncompromising commitment to liberation and a universal ethical concern for humanity.

Fanon was both a theorist of violent revolt and a humanist who ultimately fought for a world of new human relations.

Reading Shatz’s account, one realises that Fanon’s work does not give easy comfort to either the outright pacifist or the militant.

In this way, The Rebel’s Clinic uses Fanon’s ideas as a mirror to our contemporary debates, revealing the limits of liberal anti-imperialism while also probing the excesses of revolutionary purism.

Shatz himself, as a writer and thinker, appears to be testing how far a principled liberal anti-imperialist can go.

He clearly sides with the oppressed; he even validates their resort to arms under certain conditions; a stance many mainstream liberals would shy away from.

But he stops short of endorsing an “any means necessary” approach.

Between the ruins of Gaza and the ghosts of Algiers, The Rebel’s Clinic, even when it doesn’t fully cater to the radical interpretations of Fanon, still howls with defiance, demanding we face the cost of freedom without flinching, and fight for a future unrecognisable to our enemies.

Shatz’s book is definitely worth reading, and re-reading.

Its concluding message is a reminder to view Fanon not as a saint or a warmonger, but as a guide who can help us navigate the perilous journey to genuine liberation.

Until a new, fair world renders Fanon’s ideas unnecessary, we will continue to find comfort, challenge, and guidance in his ideas.