It was an afternoon of several cruel ironies.

With the genocide in Gaza reaching barely fathomable levels of brutality over the past several days, including a UN warning about the imminent deaths of up to 14,000 infants, US President Donald Trump accused South Africa of conducting a “white genocide”.

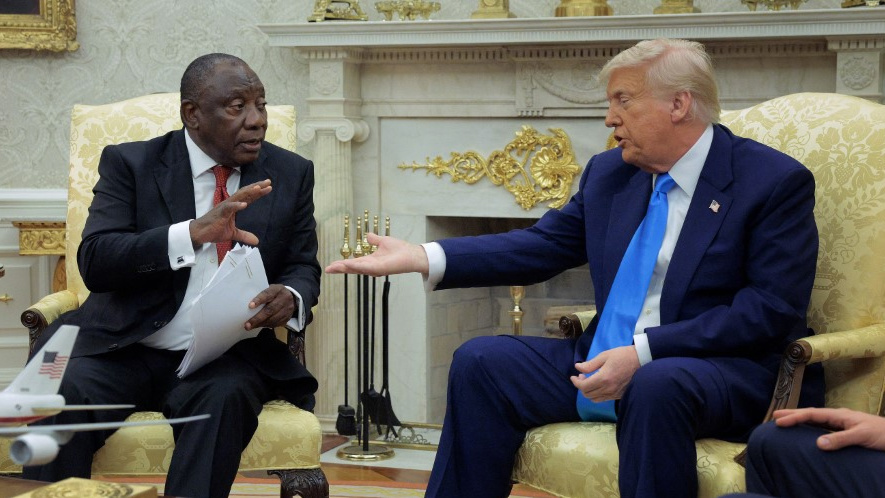

Trump, not known for his deference, flat out asked South African President Cyril Ramaphosa to explain the killings of white farmers in the country.

Ramaphosa could do little more than push back gently and offer a nervous smile as he tried to extricate himself from the televised ambush.

But Trump persisted, apparently seeking confrontation or capitulation. Trump said white South Africans were “fleeing because of the violence and racist laws”, pointing to images that showed “genocide” was taking place.

Trump asked his aides to lower the lights, and proceeded to screen a video of South African opposition party leader Julius Malema demanding land expropriation at a session in parliament.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In another video, Malema is seen leading a chant of “Kill the Boer”, referring to white farmers, a slogan that harkens back to the days when it was used to mobilise against apartheid rule. The next video, Trump said, showed “burial sites” of “over 1,000” white farmers in South Africa.

Beyond fear-mongering

For the record, not only is there no white genocide taking place in South Africa, but white South Africans own more land; have access to better schooling, healthcare and employment opportunities; and enjoy a better overall standard of living than Black South Africans.

White South Africans, who make up around seven percent of the population, own 72 percent of the country’s farmland, compared with four percent for Black Africans, who comprise 81 percent of the population.

The burial sites Trump mentioned were actually white crosses used during a protest in 2020 to represent farmers allegedly killed.

Why so many white South Africans are reluctant to support Palestine

Read More »

Throughout the public interrogation, Ramaphosa, though visibly perplexed, maintained his composure, and resisted the urge to self-immolate, as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenksy had done during a previous ambush by Trump and Vice President JD Vance in February.

It seems Ramaphosa came prepared, given that both Trump and his close associate, Elon Musk, had been circling South Africa for several months.

For Musk, who refuses to comply with South African laws mandating that at least 30 percent of a company’s ownership or economic involvement must include Black South Africans, the launch of Starlink in the country remains in purgatory.

The effort to shame South Africa, as emphasised by the arrival of 54 white “refugees” in the US earlier this month, was more than just fear-mongering. Even prior to Trump’s return to the White House, the Biden administration had made its displeasure known over Pretoria’s decision to take Israel to the International Court of Justice on the charge of genocide.

Israel, too, has used its lobbyists in an attempt to dent South Africa’s reputation in Washington. And what better obfuscation could there be than Washington accusing South Africa itself of conducting a genocide?

Win-win scenario

Earlier this year, the South African government passed a land expropriation law in an effort to reduce unequal distribution of land among the country’s people.

Amid accusations that this could result in private land being seized without payment, Ramaphosa’s office issued a statement describing it not as a “confiscation” scheme, but rather as “a constitutionally mandated legal process that ensures public access to land in an equitable and just manner as guided by the Constitution”.

Shortly after the expropriation law passed in January, Zsa-Zsa Temmers Boggenpoel, a law professor at Stellenbosch University, noted in a column: “I am not convinced that the act, in its current form, is the silver bullet to effect large-scale land reform – at least not the type of radical land reform that South Africa urgently needs.” While the law would have a “severe impact” on property rights, she added, there would be only “very limited cases” where landowners would not be compensated.

The ‘white genocide’ claim tapped into his Maga support base, reinforcing white supremacist beliefs

Though no land has been taken by the state without compensation, Trump’s administration in February froze aid to South Africa over claims of “unjust racial discrimination”.

Trump had initially waded into this topic in August 2018, when he announced that Mike Pompeo, then the US secretary of state, had been told to look into “land and farm seizures” and “large scale killings of white farmers” in South Africa.

These comments were surely influenced by a slew of right-wing American news programmes spotlighting unsubstantiated claims about an epidemic of white farmers being killed in South Africa – even as a Washington Post analysis of crime stats in the country found that farmers were “far less likely to be the targets of violent crime than the general population”.

For Trump, though, it was a win-win scenario.

The “white genocide” claim tapped into his Maga support base, reinforcing white supremacist beliefs about a community supposedly under siege.

The Southern Poverty Law Center described Trump’s 2018 move as troubling “because it signifies the mainstreaming of white nationalist narratives about ‘white genocide’, of which South Africa’s farm murders are an essential component”.

Other groups concerned about the rise of white supremacy in the US during Trump’s first term also weighed in.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) rejected as “false” the notion of a “white genocide” in South Africa, noting in a statement: “Some white farmers are actually killed each year in South Africa – as are many black farmers and many other South Africans, largely because South Africa is a country with generally high rates of violent crime … For decades, white supremacists globally were cheerleaders for the institutionalized white supremacy of apartheid in South Africa. They have reacted bitterly to the end of the racist policy, and to the progress South Africans have made in pursuit of racial equality and reconciliation.”

Notably, the pro-Israel ADL has not issued a statement condemning the latest claims of “white genocide”. Trump’s obfuscation of the actual genocide in Gaza serves its interests.

Painful irony

Ramaphosa is not guiltless in all of this.

The South African president is forever linked with the massacre of 34 Black miners in the small mining town of Marikana in 2012.

Ramaphosa, who was not president at the time, was cleared of any wrongdoing by a commission of inquiry. But for many, his role as a director and shareholder at the Lonmin platinum mine, where police shot dead the Black workers at the behest of white capital, is difficult to reconcile.

During Ramaphosa’s visit to the White House on Wednesday, a reporter asked Trump what it would take for him to change his mind on the “white genocide” issue.

The new fascism: Israel is the template for Trump and Europe’s war on freedom

Read More »

“It will take President Trump listening to the voices of South Africans, some of whom are his good friends,” Ramaphosa said.

That Ramaphosa is seen to have emerged from this interaction with his reputation intact – perhaps even enhanced – after deftly sidestepping accusations that he is overseeing a “white genocide”, while he runs a country where life remains inordinately difficult for Black people as part of the lasting legacy of colonialism and white supremacist rule, is not just irony; it is a cautionary tale.

Last year, the unemployment rate among Black South Africans was around 38 percent, compared with eight percent for white South Africans.

In a story that involves high levels of inequality, high crime rates, and a systemic lack of opportunities for the majority, it is still white fears – those that once justified apartheid – that the Black South African president must palliate.

That he knew, too, that even three decades after apartheid ended, two white South African golfers and a billionaire businessman were his best chance to assuage a US president’s “concerns” over a non-existent “white genocide” – all to facilitate the sale of critical minerals – is surely the most painful irony of them all.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.