Former CIA Director George Tenet thought him “at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden” and former Mossad Chief Shabtai Shavit regretted not killing him.

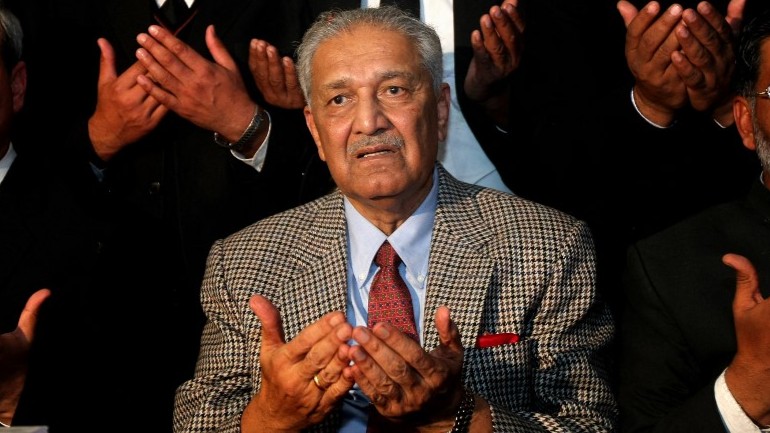

But to almost 250 million Pakistanis, Abdul Qadeer Khan – the godfather of Pakistan’s nuclear programme – is a legend and national hero.

The nuclear scientist, who was born in 1936 and died in 2021 aged 85, was more responsible than anyone else for the South Asian nation developing a nuclear bomb.

He ran a sophisticated and clandestine international network assisting Iran, Libya and North Korea with their nuclear programmes.

One of those nations, North Korea, ended up getting the coveted military status symbol.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Israel – itself a nuclear power, although it has never admitted it – allegedly used assassination attempts and threats to try and stop Pakistan from going nuclear.

In the 1980s Israel even formulated a plan to bomb Pakistan’s nuclear site with Indian assistance – a scheme that the Indian government eventually backed out of.

AQ Khan, as he is commonly remembered by Pakistanis, believed that by building a nuclear bomb he had saved his country from foreign threats, especially its nuclear-armed neighbour India.

Today many of his fellow citizens agree.

‘Why not an Islamic bomb?’

Pakistan first decided to build a bomb after its larger neighbour had done so. On 18 May 1974 India tested its first nuclear weapon, which it codenamed Smiling Buddha.

Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto immediately vowed to develop nuclear weapons for his own country.

“We will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own,” he said.

There was, he declared, “a Christian bomb, a Jewish bomb and now a Hindu bomb.

“Why not an Islamic bomb?”

‘We will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own’

– Pakistani PM Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (from 1973 to 1977)

Born during British rule of the Indian subcontinent, AQ Khan completed a science degree at Karachi University in 1960 before studying metallurgical engineering in Berlin. He also went on to study in the Netherlands and Belgium.

By 1974 Khan was working for a subcontractor of a major nuclear fuel company, Urenco, in Amsterdam.

The company supplied enriched uranium nuclear fuel for European nuclear reactors.

Khan had access to top secret areas of the Urenco facility and blueprints of the world’s best centrifuges, which enriched natural uranium and turned it into bomb fuel.

In January 1976 he made a sudden and mysterious departure from the Netherlands, saying he had been made “an offer I can’t refuse in Pakistan”.

Khan was later accused of having stolen a blueprint for uranium centrifuges, which can turn uranium into weapons-grade fuel, from the Netherlands.

That July he set up a research laboratory in Rawalpindi which produced enriched uranium for nuclear weapons.

For a few years the operation proceeded in secret. Dummy companies imported the components Khan needed to build an enrichment programme, the official story being that they were going towards a new textile mill.

While there is significant evidence indicating that Pakistan’s military establishment was supporting Khan’s work, civilian governments were generally kept in the dark, with the exception of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (who had proposed the initiative).

Even the late prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s daughter, was not told a word about the programme by her generals.

She only found out about it in 1989 by accident – in Tehran.

Iranian President Rafsanjani asked her whether they could reaffirm the two countries’ agreement on “special defence matters”.

“What exactly are you talking about, Mr President?” asked Bhutto, confused.

“Nuclear technology, Madam Prime Minister, nuclear technology,” replied the Iranian president. Bhutto was stunned.

Assassination attempts and threats

In June 1979, the operation was exposed by the magazine 8 Days. There was an international uproar. Israel protested to the Dutch, who ordered an inquiry.

A Dutch court convicted Khan in 1983 for attempted espionage (the conviction was later overturned on a technicality). But work on the nuclear programme continued.

By 1986, Khan was confident Pakistan had the capability to produce nuclear weapons.

‘Imperial whore’: Top Pakistani official goes after son of overthrown shah of Iran

Read More »

His motivation was in large part ideological: “I want to question the holier-than-thou attitude of the Americans and British,” he said.

“Are these bastards God-appointed guardians of the world?”

There were serious efforts to sabotage the programme, including a series of assassination attempts widely understood to have been the work of Israel’s intelligence agency, Mossad.

Executives at European companies doing business with Khan found themselves targeted. A letter bomb was sent to one in West Germany – he escaped but his dog was killed.

Another bombing targeted a senior executive of Swiss company Cora Engineering, which worked on Pakistan’s nuclear programme.

Historians, including Adrian Levy, Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Hanni, have argued that the Mossad used threats and assassination attempts in a failed campaign to prevent Pakistan from building the bomb.

Siegfried Schertler, the owner of one company, told Swiss Federal Police that Mossad agents phoned him and his salesmen repeatedly.

He said he was approached by an employee of the Israeli embassy in Germany, a man named David, who told him to stop “these businesses” regarding nuclear weapons.

The Israelis “didn’t want a Muslim country to have the bomb”, according to Feroz Khan, a former official in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme.

‘Are these bastards God-appointed guardians of the world?’

– AQ Khan, Pakistani nuclear scientist

In the early 1980s Israel proposed to India that the two collaborate to bomb and destroy Pakistan’s nuclear facility at Kahuta in Pakistan’s Rawalpindi district.

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi approved the strike.

A plan developed for Israeli F-16s and F-15s to take off from the Jamnagar airbase in India’s Gujarat and launch strikes on the facility.

But Gandhi later backed out and the plan was shelved.

In 1987, when her son Rajiv Gandhi was prime minister, the Indian army chief Lieutenant General Krishnaswami Sundarji tried to start a war with Pakistan so India could bomb the nuclear facility at Kahuta.

He sent half a million troops to the Pakistani border for military drills, along with hundreds of tanks and armoured vehicles – an extraordinary provocation.

But this attempt at triggering hostilities failed after the Indian prime minister, who had not been properly briefed on Sundarji’s plan, instigated a deescalation with Pakistan.

Despite Indian and Israeli opposition, both the US and China covertly helped Pakistan. China provided the Pakistanis with enriched uranium, tritium and even scientists.

Meanwhile, American support came because Pakistan was an important Cold War ally.

US President Jimmy Carter cut aid to Pakistan in April 1979 in response to Pakistan’s programme being exposed, but then reversed the decision months later when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan: America would need the help of neighbouring Pakistan.

In the 1980s, the US covertly gave Pakistani nuclear scientists technical training and turned a blind eye to its programme.

But everything changed with the end of the Cold War.

In October 1990 the US halted economic and military aid to Pakistan in protest against the nuclear programme. Pakistan then said it would stop developing nuclear weapons.

AQ Khan later revealed, though, that the production of highly enriched uranium secretly continued.

The seventh nuclear power

On 11 May 1998 India tested its nuclear warheads. Pakistan then successfully tested its own in the Balochistan desert later that month. The US responded by sanctioning both India and Pakistan.

Pakistan had become the world’s seventh nuclear power.

And Khan was a national hero. He was driven around in motorcades as large as the prime minister’s and was guarded by army commandos.

What the Israel-Iran-US conflict taught Pakistan

Read More »

Streets, schools and multiple cricket teams were named after him. He wasn’t known for playing down his achievements.

“Who made the atom bomb? I made it,” Khan declared on national television. “Who made the missiles? I made them for you.”

But Khan had also organised another, particularly daring, operation.

From the mid-1980s onwards, he ran an international nuclear network which sent technology and designs to Iran, North Korea and Libya.

He would order double the number of parts the Pakistani nuclear programme required and then secretly sell the excess on.

In the 1980s the Iranian government – despite Ayatollah Khomeini’s opposition to the bomb on the grounds that it was Islamically prohibited – approached Pakistan’s military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq, for help.

Between 1986 and 2001, Pakistan gave Iran key components needed to make a bomb, although these tended to be secondhand – Khan kept the most advanced technology for Pakistan.

The Mossad had Khan under surveillance as he travelled around the Middle East in the 1980s and 1990s, but failed to work out what the scientist was doing.

Then-Mossad chief Shavit later said that if he had realised Khan’s intentions, he would have considered ordering Khan to be assassinated to “change the course of history”.

Gaddafi exposes the operation

In the end, Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi blew Khan’s operation in 2003 while attempting to win support from the US.

Gaddafi disclosed to the CIA and MI6 that Khan was building nuclear sites for his government – some of which were disguised as chicken farms.

The CIA siezed machinery bound for Libya as it was being smuggled through the Suez Canal. Investigators found weapons blueprints in bags from an Islamabad dry cleaner.

When the operation was exposed, the Americans were horrified.

“It was an astounding transformation when you think about it, something we’ve never seen before,” a senior American official told the New York Times.

“First, [Khan] exploits a fragmented market and develops a quite advanced nuclear arsenal.

“Then he throws the switch, reverses the flow and figures out how to sell the whole kit, right down to the bomb designs, to some of the world’s worst governments.”

In 2004 Khan confessed to running the nuclear proliferation network, saying he had provided Iran, Libya and North Korea with nuclear technology.

In February, he appeared on television and insisted he had acted alone, with no support from the Pakistani government, which then swiftly pardoned him.

President Musharraf called him “my hero”. However, reportedly under US pressure, he placed Khan under effective house arrest in Islamabad until 2009.

Later AQ Khan said that he “saved the country for the first time when I made Pakistan a nuclear nation and saved it again when I confessed and took the whole blame on myself”.

He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2006 but recovered after surgery.

Enormously wealthy, in his later years, Khan funded a community centre in Islamabad and spent his time feeding monkeys.

Those who knew him said Khan firmly believed what he had done was right.

He wanted to stand up to the west and give nuclear technology to non-western, particularly Muslim, nations.

“He also said that giving technology to a Muslim country was not a crime,” one anonymous acquaintance recalled.

When Khan died of Covid in 2021, he was hailed as a “national icon” by then-Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan.

And that is how he is still widely remembered today in Pakistan.

“[The] nation should be rest assured Pakistan is a safe atomic power,” the nuclear scientist had declared in 2019.

“No one can cast an evil eye on it.”